Remembering Tejano East Austin

Originally published in CAP Magazine February 2014.

Can The Tejano Trails Project save the community’s place in history?

You may have heard that Austin is booming. The city ranks just fifth in the United States for number of tech start-ups, and second in the nation for jobs in those start-ups. The crime rate’s low, houses are cheap—just fifteen percent below the national average—property values are on the rise (so buy now!), and just about 160 people are moving here daily. And therein lies the problem: As capital pours into the city through the new residents and new companies and new developers, many of Austin’s neighborhoods—especially historically African-American and Latino neighborhoods—face the risk of cultural and historical erasure. And right now, everyone has their sights set on East Austin.

East Austin is a location so prime, so hip, that each new resident is basically handed keys to their own craft cocktail lounge upon arrival. As evidenced by the erection of new condos and luxury lofts, the developers are well aware that this is where people want to be. Many of Austin’s unofficial landmarks in other areas have gone the way of the bulldozer. South Austin’s already gone through much of this change. The beloved food truck park on South Congress is now the future site of a boutique hotel. Blink and you’ll miss the sign for the famous honky-tonk, The Broken Spoke, as it peeks between the facades of two major apartment complexes, also still in construction. East Austin is no different. It seems a new building pops up everyday.

But there was an East Austin before all of the cocktail lounges and upscale living, and the residents of the East Cesar Chavez neighborhood want everyone to know that before every last building is torn down.

The East Cesar Chavez neighborhood—the downtown-adjacent area of East Austin between I-35 and Chicon from west to east, and Town Lake to East 7th Street from south to north—is a historically Mexican-American district dating back to the early twentieth century. The native population of the neighborhood is comprised of mixed income residents, including retirees who have lived in the community for decades.

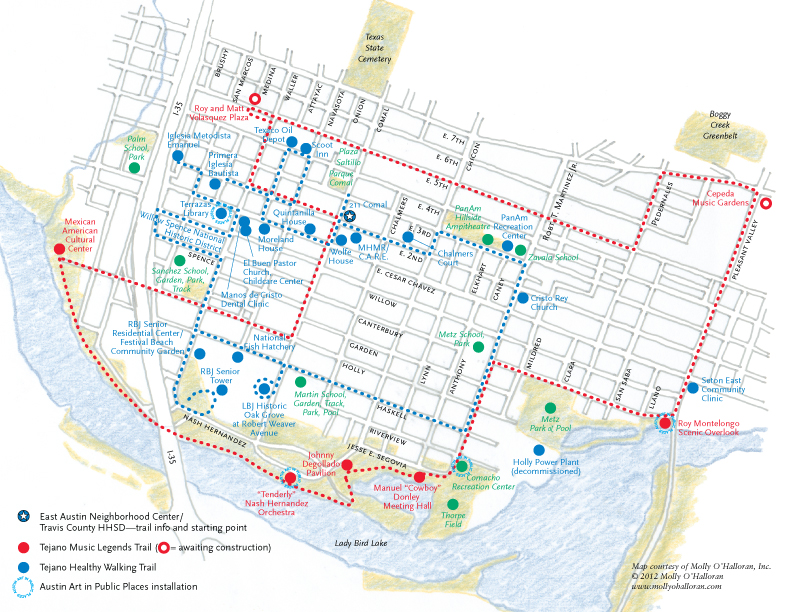

In order to address the issues surrounding the current development of East Cesar Chavez, the East Cesar Chavez Neighborhood Planning Team, with the help of the City Council, developed the Tejano Healthy Walking Trail in May 2012, after years of planning. The Walking Trail is a five-mile urban trail through the neighborhood that features all but forgotten landmarks, such as old churches, Victorian homes, early affordable housing units, and the National Fish Hatchery. In addition to the Healthy Walking Trails, the Austin Latino Music Association developed the Tejano Music Legends trail, which highlights prominent Latino musicians from East Cesar Chavez who were instrumental in building Austin’s “live music” identity.

The Planning Team developed the trail with three goals in mind: “Preserve historic structures and affordable homes;” “[e]ducate speculators and newcomers about the historic assets in hopes they might choose to upgrade old structures rather than destroy them;” and to “[e]ncourage a healthier lifestyle, especially for youth who rarely bike, walk or exercise.”

When I embarked on the five mile trail, the second stop, El Jardin Alegre (The Happy Garden) community garden, was no longer there. Instead, mounds of dirt and a few structural beams marked the sprouts of a brand new, deluxe condo development. This set the tone of the tour, which featured many still-standing reminders of the neighborhood’s past, but was also peppered with new, somewhat lavish homes that were more befitting of a Tetris game, rectangular in shape, lime green in color, rather than a family neighborhood—the architecture of which was primarily Victorian, with bay windows and large porches.

East Cesar Chavez is an area that’s no stranger to development. Primarily a European district in the nineteenth century, Mexican-Americans moved to the area in the 1920s and 30s as a result of Downtown Austin’s expansion. When I-35 was built in the 1950s, taking the place of East Avenue, the community became isolated on a cultural and socioeconomic level. Most of the white population promptly moved westward.

Like so many marginalized communities, the area was neglected by local government, and many of the families were left in squalor. Few houses had indoor plumbing by the mid-twentieth century, and few resources were available for the people of the community to bring about positive change to the area. But the East Cesar Chavez neighborhood was bolstered by Lyndon B. Johnson’s advocacy as a state congressman and senator.

Many featured stops on the tour were developed as a result of Lyndon B. Johnson’s efforts as a Texas senator through the Great Society program. The Chalmers Court Apartments, built in 1939, were one of the first three affordable housing developments in the United States. The RBJ Clinic and Senior Residential Center, named for President Johnson’s mother, Rebekah Baines Johnson, is a sixteen-story high rise developed in the late 1960s built as a model for affordable and assisted living for senior citizens. A true relic of its era, the National Fish Hatchery has all but disappeared, leaving behind a small manmade pond—now empty—and two white columns that mark its Grand Entrance.

“[East Cesar Chavez] was LBJ’s experimental playground,” said Lori Renteria, the Tejano Trails coordinator and member of the East Cesar Chavez Neighborhood Planning Team. “Being a schoolteacher and overlooking [homes where] they didn’t even have indoor plumbing was a real concern.” Johnson’s legacy in the neighborhood is rooted in the affordable housing projects and veteran occupational training programs established before and after World War II.

Indeed, much of the area’s development for the better part of the twentieth century was for the benefit of the lower-income, Mexican-American residents. But now, further development threatens that very legacy of Lyndon B. Johnson, as well as the Neighborhood Planning Team.

Of course, you can’t simply stop the new (young, affluent, white) demographic from moving into the neighborhood. Instead, the East Cesar Chavez Neighborhood Association proposes sustaining the current population by keeping housing affordable. New residents are encouraged to familiarize themselves with the history and become active members of the community. In addition, they urge developers to preserve the history of the area by updating the present architecture rather than destroying it and rebuilding with sleek, new condominiums and restaurant space that don’t fit with the character of the area.

History is a tool of power and dominion written, as the adage asserts, by the victors. In the event that nothing is preserved in the aggressive development of the neighborhood, what the Tejano Trails project offers is a different point of view—a reminder that a thriving neighborhood built on the principles of affordability and community, not privilege and capital, once existed.

The Tejano Trails project is a site of resistance to the “brigade of bulldozers heading east,” as Lori puts it. “We decided that, if we can’t win the battle to save the historical structures and the historical diversity of the neighborhood, then at least we can have trail markers that say ‘There used to be a Pan-American Recreation Center here.’” The historical preservation of East Austin, even if only through signage, functions as a way to maintain the narrative of the community, not only as a remembrance of the past, but also as a method of interrogating the present.

For every new structure that is constructed and every demolished home that remains beneath the foundation, a piece of a culture is concealed. As the decades go by, and progress remains unquestioned, the affluent, white population of the neighborhood is normalized. The thriving Mexican-American community of the twentieth century becomes an afterthought. However, if the mission of the Tejano Trails project is a success, newcomers and developers will see the importance of preserving the diverse, mixed-income community, and the folly of paving over the history of not only a neighborhood, but of an entire city.

While Austin’s momentum appears unstoppable, Lori remains hopeful for the future of the Tejano Trails and East Cesar Chavez. The Trails were recently granted National Recreational Trail status from the Department of the Interior. That enabled them for the National Park Service’s Rivers, Trails, and Conservation Assistance program, which will help the program expand and improve. “The more people we get walking the neighborhood and seeing all this history … we think it’ll work,” Lori assured me.

But if everything goes south—or east, as it were—at least the East Cesar Chavez community will have had a fighting chance at writing their own history.◥